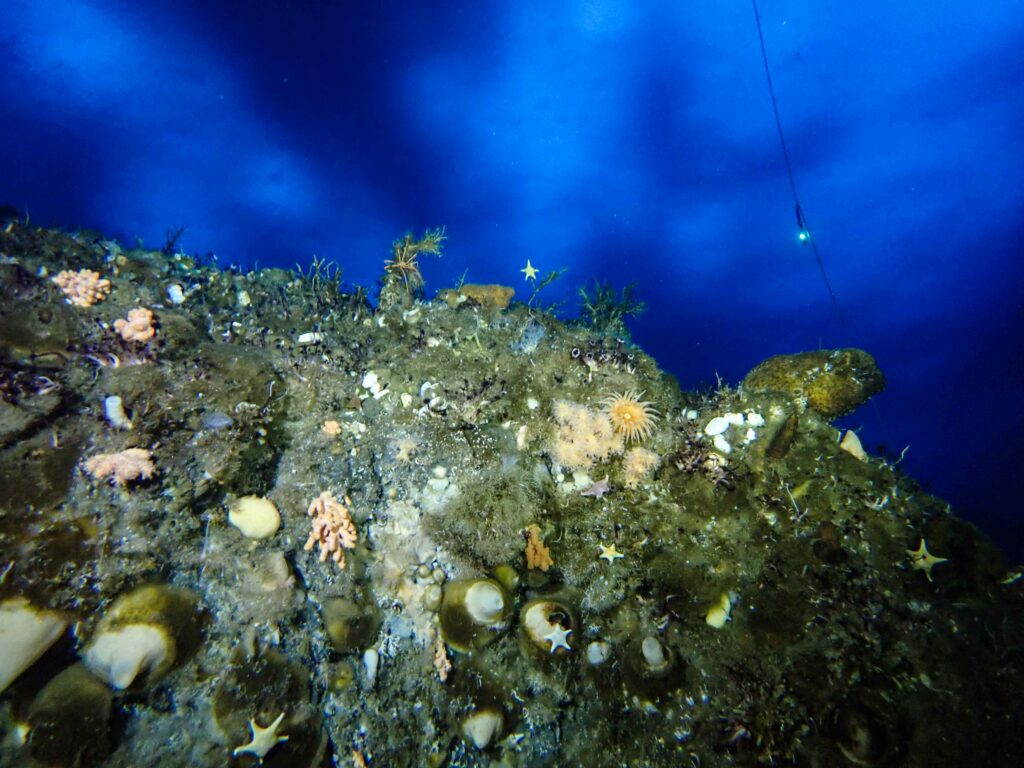

We’ve been starting to show you images of what the icy surface of the Ross Sea looks like from below, but some of the most fascinating things we’ve seen are actually on the seafloor. Not everyone is aware of the fact that there’s actually a rich community of organisms living in these waters, and rightfully so! It’s pretty impressive that their existence is possible in a world that lacks any light and food from algae for many months of the year.

The last two days I have taken a break from sample collection tasks and have instead been taking down a camera. Although there’s much more living on the seafloor than I could possibly take pictures of, I’d like to introduce you to a few of the animals we sea regularly.

Believe it or not, we’re not just collecting mud and water for microbes, we’re also collecting three animals. Odontaster sea stars, Sterechinus sea urchins, and Parborlasia nemertean worms (they look and smell like intestines). Part of what we’re interested in researching here is whether animals like these eat the microbes we study as a food source. Some of the ways we figure that out are by sequencing the genes in their guts to see what microbes are inside and by analyzing their body tissues for signatures of those unique microbes. You really are what you eat!

Most of the organisms living on the seafloor and in the water are invertebrates – animals without a backbone like the worms, anemones, and nudibranchs below. Most of them get food by filtering through the sediments and water for anything edible and expelling the rest. Whenever we dissect a sea star or urchin there’s a brown gut running through much of their bodies, filled with mud being processed for anything that might be of value.

While picking out red sea stars to sample is easy, sometimes at first glance it’s hard to tell which spineless animal you’re looking at, even at a broad level. This bryozoan (a colonial invertebrate), for example, looks similar to some sponges, which are an entirely different group of animals. Rowan is sampling these for a potential project of hers – stayed tuned for more in a future post.

Other things are really apparent, like this neon spiky yellow sponge, although even these are hard to tell apart to species level with multiple species looking alike.

And yes, although invertebrates may be my personal favorite for all their complex and fascinating anatomy, so drastically different from our own, there are also fish. And down here, they too have fascinating adaptations. Many fish here, such as the Trematomus bernacchii below, have anti-freeze proteins in their blood allowing them to live in the almost -2 degree Celsius water that characterizes their environment.

And then there’s us! Totally out of place, using 100+ pounds of gear and other technology to cheat our way into an environment for which our bodies are comically ill-adapted. Taking pictures in a place where we shouldn’t be able to breathe, adjust our buoyancy, or see well. I’m grateful to be here in this alien world, bringing photos back for you all to enjoy!