Today we dove at Turtle Rocks, which is a wonderful dive site. But it has a big problem – there is just too much life on the seafloor. Everywhere you look there are sponges, sea slugs, and tons of feather duster worms. Even the sponges are covered with other things (like you can see the yellow sponge covered with tons of different life).

The whole places is covered by life. Tons of our favorite red seastars and then all the stuff they eat from moss animals (bryozoans) to lots of microscopic algae that capture what little sunlight makes it through the ice.

All of those little white structures are the feeding structures of segmented worms (feather dusters/ sabellid polychaetes) that capture food from the water. If you look close at the lower left of the image you just see TONS of them.

Thankfully some of them stand out enough to contrast with the other colors on the seafloor.

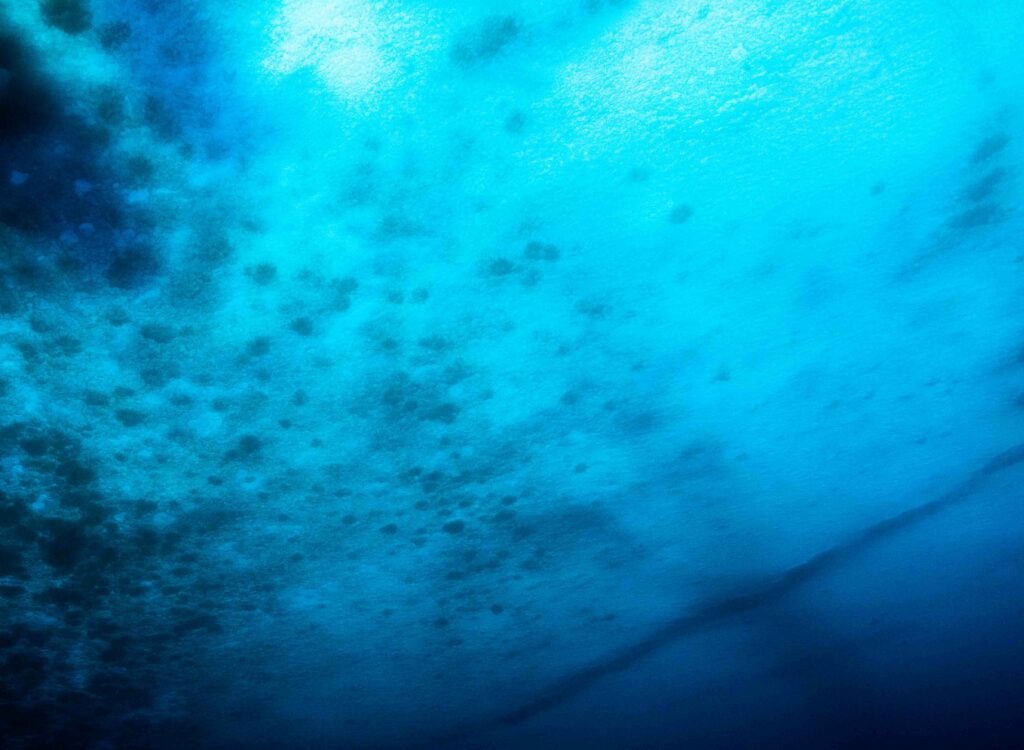

But then when you look up, even more life. Each one of those little patches are ice algae that are growing on the bottom of the sea ice. It looks to me like a petri dish from a microbiology lab.

And that is one of the wonderful contrasts of Antarctica. Ice, more ice, and a bit of ice on the surface. Maybe a penguin or seal. Maybe a wee titch of black rock. But underwater is a myriad of colors and life soo crowded that it muddies the photos with diversity. Not a bad problem to have, but it can make some of the photos harder to stand out.